1998: Back when I considered Zen Buddhism - Part 2

In which Teófilo continues reminiscing about a short span of his life that he now shakes his head at.

There are various things that made Buddhism attractive to me. I can explain Buddhism better if I think of it as a religion, a philosophy, a way of thinking, or even as a system of ethics without belief in gods. I elucidated all these and wish to record it for posterity.

Buddhism as a religion

Buddhism has all the incense, bells, and whistles you may want to find in a ritual religion. It doesn't matter how bereft and, let's say, puritan a school of Buddhism might be, it'll have some ritual mixed in it. Buddhists of all stripes chant, play sacred music, wear liturgical robes, etc.

Buddhists also build temples, venerate saints and hold pilgrimages to their holy sites. They engage in processions, have their own diet and fasting rituals, and haircuts. They read their scriptures in a variety of media, which they venerate. Their scholars rigorously analyze their scriptures, just like scholars at Western institutions do. They engage all the highest critical tools in pursuit of understanding them.

Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, accepted the Hindu pantheon of gods as a matter of course. In this sense, Buddhism isn't "atheistic" as some claim. Then again, the Buddha admitted these deities into system with a unique twist: he demoted them. He made them less important.

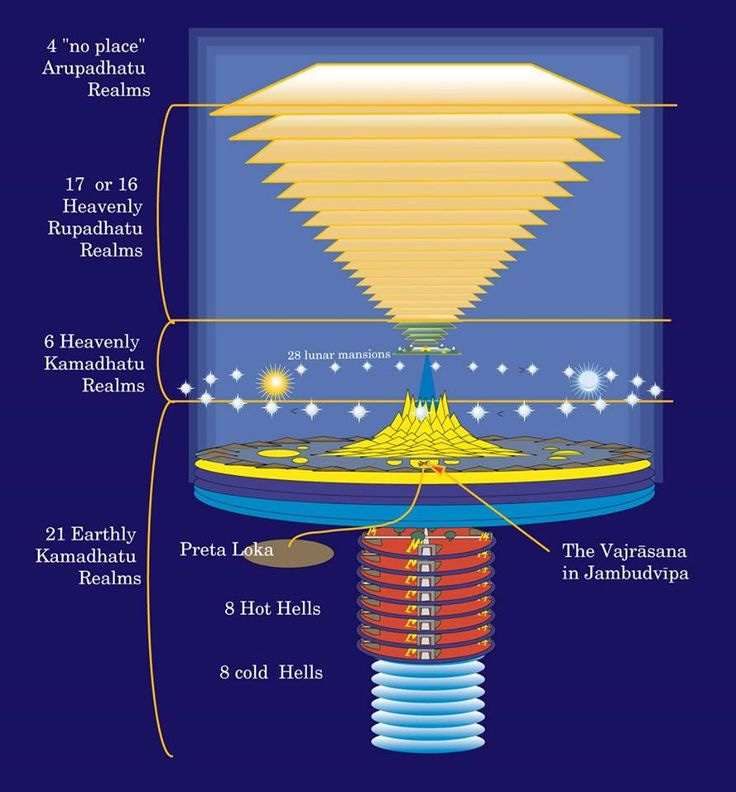

Buddha taught that his law of impermanence applied to the Hindu deities themselves. That is, applying this law made these deities impermanent and as a consequence, mortal. They are exalted beings, yes, but subjected to decay and disintegration in the very long run. Even deities had to follow the Buddha's teachings to escape the cycle of rebirth. Why worship a deity when following the Buddha's path frees one's spirit from the wheel of rebirth forever? Even so, a Buddhist won't chide another Buddhist if they choose to worship a deity. If they need to, fine. If it helps a devotee achieve a better, future rebirth and find enlightenment, that's great. Or the devotee may reach one of several "heavenly planes" and reach enlightenment while there. That too is good.

Buddhist "salvation, anthropology, and theology

It's oft said that the goal of Buddhism is to help its adherents to reach "nirvana." Nirvana is a state of ultimate peace and liberation from the cycle of rebirth and suffering in Buddhism. It's the highest spiritual goal, where one is free from desires, attachments, and the ego. It was also the name of a dry cleaner business in my hometown of Ponce back in the day, but I digress.

The definition above tells us nothing about the nature of "nirvana." To understand it, one must understand a bit of the Buddhist view of man, its "anthropology."

In Buddhism, man doesn't have a "soul" in the sense we teach in Christianity. This doesn't mean that they teach that humans lack an inmaterial dimension. In Buddhism, there's no permanent 'I' because the ego is always changing. They deny that there's a permanent, immaterial substance giving the body its unchanging essence. The first personal pronoun "I" only has a grammatical existence but nothing else beyond it.

Then, what is it that "reincarnates" after death if not a soul? This is where it gets tricky. Instead of a spiritual soul in a body, Buddhists see humans as a cluster of grapes. Bear with me, please.

Let's imagine that every one of one's attributes is a single grape. Our intelligence, our physiognomy, our accumulated karma from past lives, each of these attributes is a "grape." Each grape is in turn connected to a stem. When one dies, some "grapes" might fall off and others gained. Then one is reborn, but not as the same person because one's attributes are also impermanent. A man can be reborn as a woman, or woman as a man. One's sex is also subject to change and impermanence between rebirths.

But what about the stem? Doesn't it remain unchanged? Isn't the stem in some sense, the soul? No. Knowing what the nature of the stem is the big deal in Buddhist anthropology. The stem is one's desire to survive, one's attachment to the wheel of existence. But this desire too is impermanent. When someone realizes that the inner self is an illusion, they have reached enlightenment. One has thus become a Buddha. At the moment of death, all the "grapes" will dissolve as the stem dissolves into nothingness. That's nirvana.

That might not sound too attractive, but there's more. It so happens that something does remain after everything illusory falls away. What remains is pure, detached awareness. I can't say it's your awareness because there's no "you" for the awareness to attach to. But how about other "awarenesses" floating in whatever space this is; is that awareness aware of the others? Yes, but not as distinct centers of awareness. In this state, the subject-object duality also disappears. Duality too is an illusion. In this state, one's is aware of another awareness because both are the same awareness. Everyone in Nirvana exists in a state of perfect, unified awareness. What is this single awareness aware of? Of the rest of the universe, with which it's one.

Is this existence, "God" then? Not as we Christians understand God. We've inherited from Judaism the notion that God is utterly personal. God is "I AM." In Christianity, Ego is at the center of all existence as Creator, the exact opposite to the Buddhist view. God is immutable for us Christians, neither impermanent nor perishable as Buddhism would teach it. I’ll return to this central difference later on.

Let's return to Buddhism. This state of nirvana is the Buddhist endgame, its goal of salvation. Following the Buddha's Eight Noble Truths enables one to escape the cycle of existence and dissatisfaction. This escape is nirvana.

I will discuss the Buddha's Eight Noble Truths in the next installment. Nirvana and the Eight Noble Truths are core teachings common to all Buddhist traditions. I'll also discuss how similar and disimilar Buddhism and Christianity are to each other.

In Christianity, Ego is at the center of all existence as Creator, the exact opposite to the Buddhist view. God is immutable for us Christians, neither impermanent nor perishable as Buddhism would teach it.