1998: Back when I considered Zen Buddhism - Part 1.

In which Teófilo narrates a short span of his life that he now shakes his head at.

I declared theology “dead",” but not God.

At the start of 1998 I was declaring my theology background, dead. I'd declared myself a pious agnostic, a cultural Christian without dogmatic commitments. We kept attending the Orthodox church at Conemaugh borough, but my heart was no longer in it.

If the icons on my current prayer corner could speak, they would be laughing.

Despite my misgivings, I knew I needed some structure in my spiritual life - assuming still I had a "spirit." That's when I started to read about Zen Buddhism more in depth.

I've already had some theoretical experience on Zen school of Buddhism. You might recall how my Philosophy of Religion instructor had shared with us his insights on Zen. Then there were the many mentions Thomas Merton made of Zen in his journals and the books he wrote about it. Like Mystics and Zen Masters. Or Zen and the Birds of Appetite.

In Mystics and Zen Masters Merton wrote:

All these studies, are united by one central concern: to understand various ways in which men of different traditions have conceived the meaning and method of the 'way' which leads to the highest levels of religious or of metaphysical awareness.

While in Zen and the Birds of Appetite he wrote:

Zen enriches no one. There is no body to be found. The birds may come and circle for a while... but they soon go elsewhere. When they are gone, the 'nothing,' the 'no-body' that was there, suddenly appears. That is Zen. It was there all the time but the scavengers missed it, because it was not their kind of prey.

Zen was very intriguing to me at that time. I thought Zen could provide a way to arrive at mental peace. I saw it - more in a romantic vein - as a kind of logic as depicted in the sci-fi series, Star Trek.

Now, I didn't convert. I didn't pledge allegiance to The Three Jewels. I knew that was a step too far. What I did was to read, a lot.

Because I liked "orthodoxies," I sought out what I thought Buddhism's earliest tradition. This I found in Buddhism's Theravada school. Theravada means smaller vessel, as compared to Mahayana Buddhism, the larger vessel. The name suggest elitism, since few are those who embark on the little boat, as compared to the big Mahayana one. I then became a frequent reader Access to Insight, a Theravada library on the Internet.

But Zen Buddhism isn't a branch of Theravada. It is and remains a Mahayana offshoot, made in China and exported to Japan. Theravada Buddhists study their scriptures as diligently as Hasidic Jews study the Torah. The tradition emphasizes study of the Pali canon - the Tipitaka. Theravadins meditate too, and quite a lot. However, they teach that achieving enlightenment in Buddhism takes a long time and many reincarnations. That's sort of a downer.

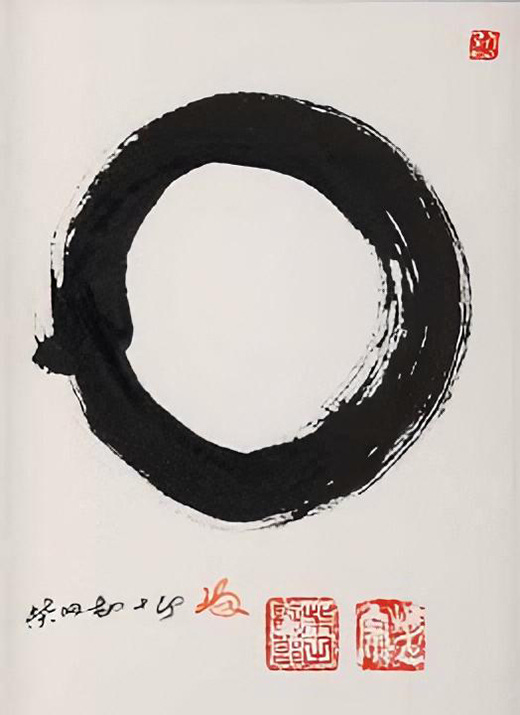

Zen Buddhism is more optimistic. Zen Buddhists study scriptures from India and China, but they also teach they can attain enlightenment in a single lifetime. In fact, Zen teachers assert their tradition is one of direct intuition into the essence of reality. Meditation is central to this quest and the very word zen means "to sit." So, I combined my study of both traditions to see where it would lead.

Afterword.

As you know, one of my favorite Zen books is a comic book. Titled, Zen Speaks, this is a work by Tsai Chih Chung. The author depicts on each page a Zen saying and its explanation. As noted by Merton and many others, a lot of these sayings approximate what the Christian Desert Fathers would’ve said in similar circumstances. This is, by far, my favorite story from Zen Speaks:

Zen practitioners don’t study scriptures, as Zen emphasizes direct experience over intellectual learning. It is a direct transmission outside the scriptures, not relying on words or letters, pointing directly to the mind, and seeing into one’s true nature to attain Buddhahood.